Caribou County, Idaho | N42° 51.862’ W111° 54.265’

5 minute read

Ghosts in the Snow

Snow crunched under my feet as I stood at the edge of Chesterfield, a Mormon ghost town in Caribou County, tucked away in a part of Idaho that seemed to be forgotten. It had snowed more than I had expected or prepared for, lacking proper boots, and when I stepped off the pavement and sank knee-deep, I knew I’d have to settle for photographing the sagging cabins and red-brick buildings from a distance. Stepping back to Chesterfield Rd., I took in a clear view of all 27 buildings still standing – dark silhouettes against the white – frozen in time like sentinels of a broken pioneer spirit. The crisp air felt heavy with stories of their lives memorialized beneath the frost.

As I lingered there, captivated by the stark abandonment of a once thriving community, the silence deepened, broken only by a windmill with rusted blades creaking in the breeze. Its relentless groan haunted the stillness, as if Chesterfield itself had been breathing, refusing to fade.

“A victim of progress”

~ Frank C. Robertson, former Chesterfield resident

A Spark in the Wilderness

Chesterfield was first settled in 1879 by Chester Call, an LDS Bishop from Bountiful, Utah and Christian Nelson, his nephew. With fire in his soul he encouraged others from Utah to join him.1 The Portneuf Valley, lush with grasses and fed by the river’s steady flow, perfect for livestock and farming, seemed to promise a new Zion.

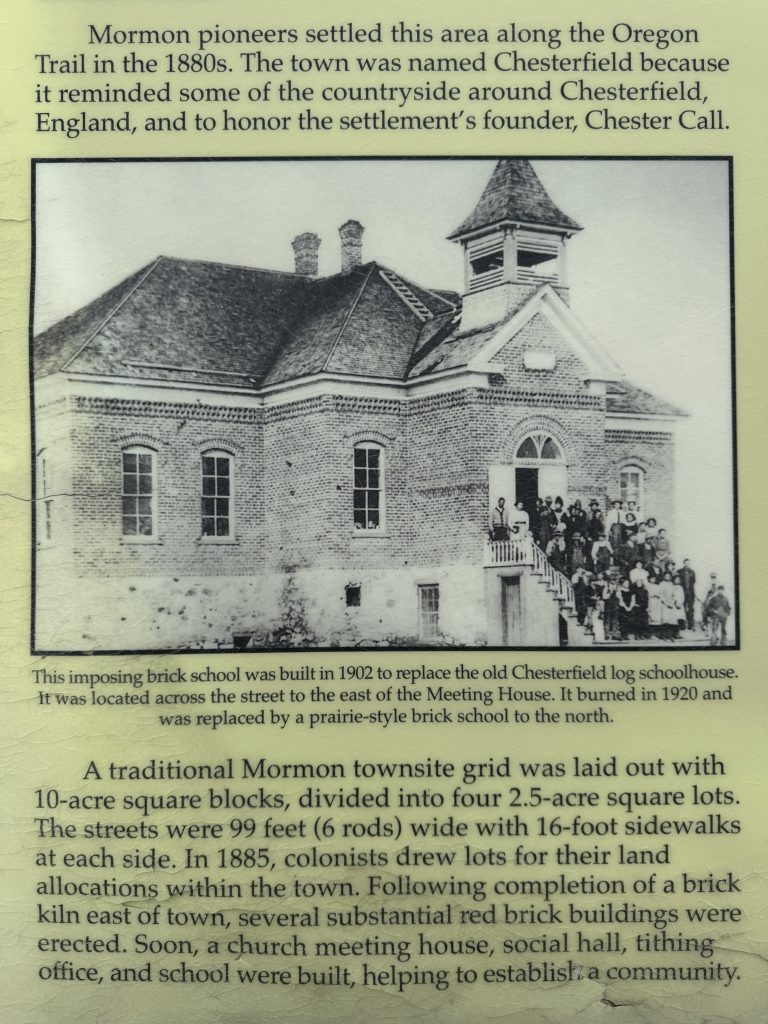

They named their outpost Chesterfield, a nod to Chester and the English hills some ancestors had left behind.2 It hadn’t been a church-ordered settlement; this was raw, stubborn hope, born of faith and grit. By 1883, those families, numbering 136 across 24 households, had organized their claims into a grid, following Joseph Smith’s “Plat of Zion” with a meetinghouse crowning the hill—its bricks fired in a local kiln.

Image courtesy of the Chesterfield Foundation

The Call family had led the charge. Chester’s adopted Native American sister, Ruth Call Davids, became the town’s midwife, delivering babies in dugouts and cabins with her herbal remedies and steady hands. Her husband, James Henry Davids, helped build the some of the earliest homes.

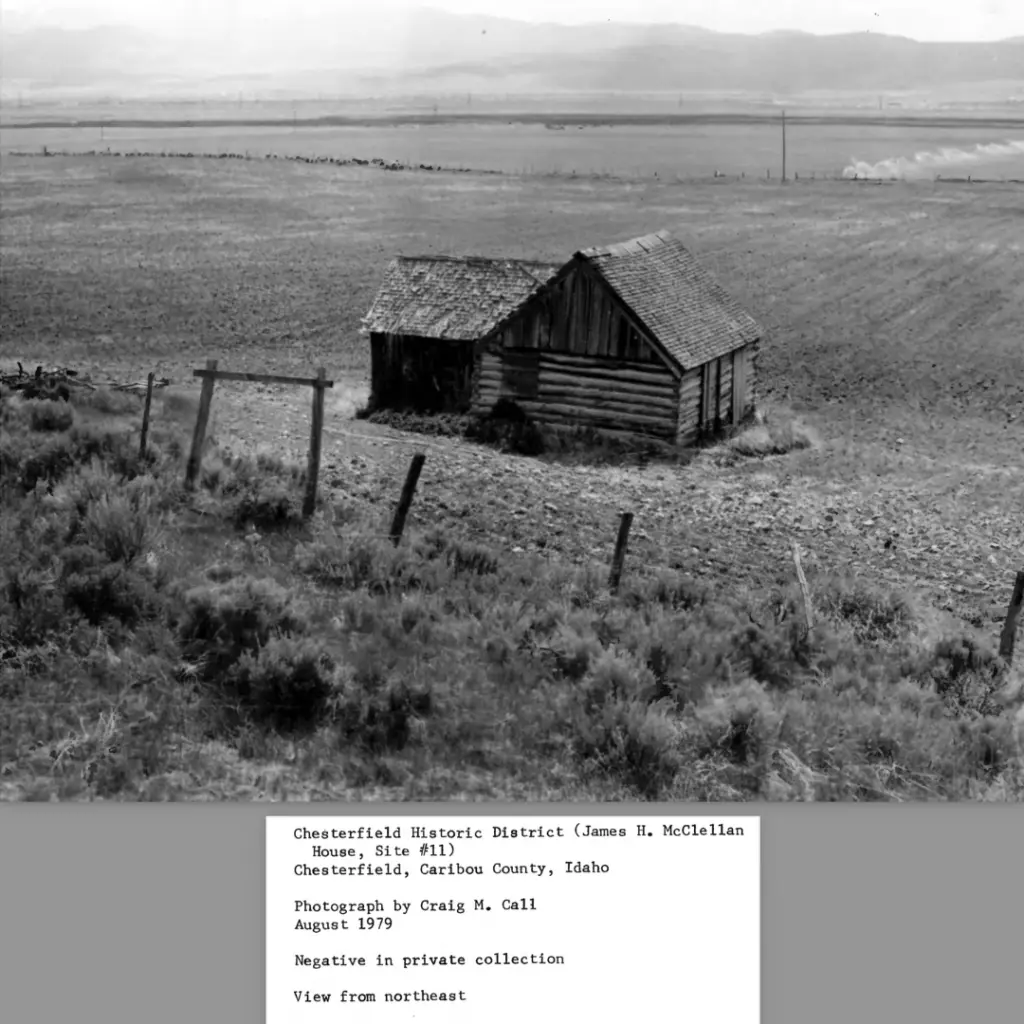

Photo courtesy of the National Register of Historic Places, 1979

James H. McClellan House, March 2025

The Tolmans, including Alice Tolman Yancey, endured winters that tested their resolve. The Reeses, with their knack for brickmaking, crafted homes that stood firm and defied time. The Yosts and Nelsons wrestled with Chesterfield’s stubborn soil, yielding crops from land that often betrayed them.

Winters grew crueler, burying homes in drifts that Alice Tolman Yancey described as towering over houses, with buildings “snapping” in the cold.

Chesterfield had hummed along the Oregon Trail, a ribbon of ruts cutting through the valley. Travelers stopped for supplies, and the settlers sold logs to the Union Pacific when the Oregon Short Line arrived in 1881. At its peak in 1920, nearly 700 people lived there, their lives busy with church meetings, harvest, dances, and the daily grind of frontier survival.

The Slow Bleed

Chesterfield’s spirit couldn’t hold. The Oregon Short Line, a Union Pacific branch completed in 1882, had bypassed Chesterfield, carving its path eight miles south through Bancroft. That single decision bled the town dry. Bancroft, with its new depot, became a magnet for commerce, drawing merchants, farmers, and dreamers who saw opportunity in the railroad’s iron lifeline.

Oregon Short Line Rail, organized in 1881

Chesterfield’s general store, once bustling with Oregon Trail travelers, grew quiet as trade shifted south. Families like the Reeses, who had bartered their bricks for goods, found fewer buyers, their wares left to gather dust. The railroad brought goods and jobs to Bancroft, but for Chesterfield, it carried away prosperity, leaving fields of empty hope.

Winters buried homes in drifts that Alice Tolman Yancey described as towering over houses, with buildings “snapping” in the cold. Summer droughts and early frosts choked crops, leaving fields barren. The Panic of 1907 tightened wallets, forcing some to sell their land.

The 1918 influenza epidemic swept through, claiming lives and leaving scars. The road to the cemetery was closed so I wasn’t able to photograph their headstones, but even from a distance, it wasn’t hard to imagine families like the Tolmans grieving next to freshly dug graves.

Chesterfield Cemetery, March 2025

The Great Depression crushed what remained, with farm prices plummeting and debts mounting. “A victim of progress,” writer Frank C. Robertson, once a Chesterfield boy, called it—a slow death by a world that no longer needed small outposts.

The population dwindled: 425 in 1928, barely 100 by 1950, and just 20 by 1970. The school closed in 1941, its bell silenced. The general store, where locals had traded stories and goods, shuttered in 1958. The last stragglers, their names unrecorded, slipped away in the late 1970s. Chesterfield faded like a photograph left in the sun – the creaking of the windmill felt like their final lament.

A Legacy Preserved

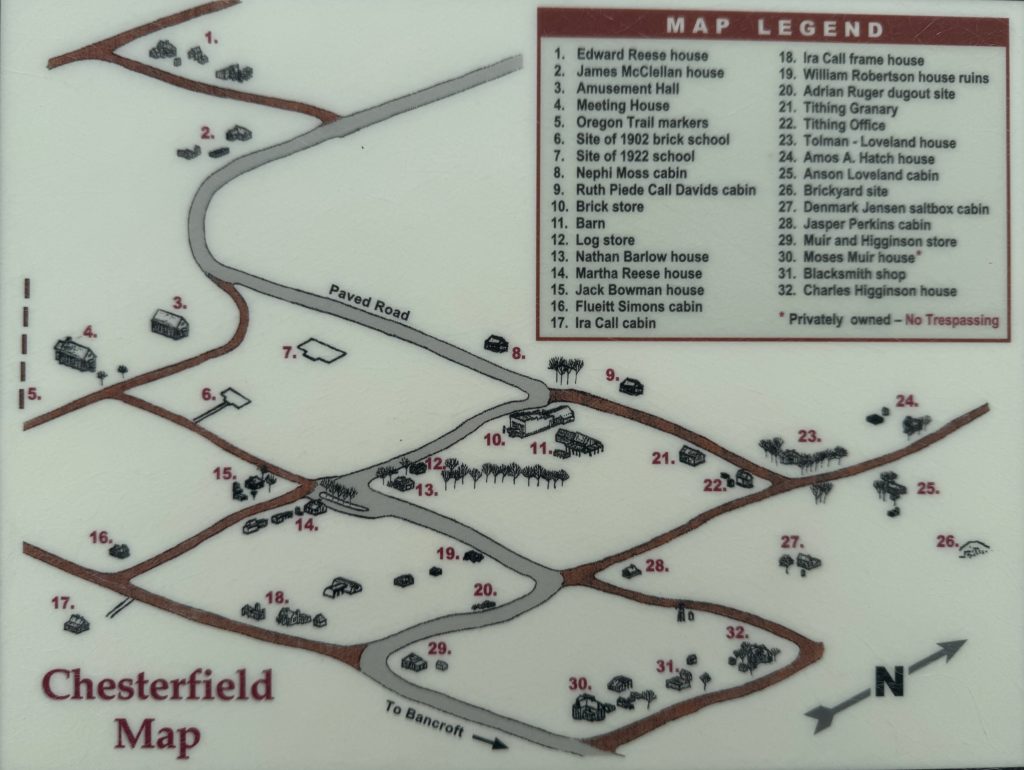

Chesterfield could’ve crumbled into sagebrush like every other ghost town in the west, but in 1979, descendants like Jack Jensen and Fred G. Yost fought back. The Chesterfield Foundation was formed and saved 27 buildings including the original LDS meetinghouse, the amusement hall, the tithing office, and the tithing granary. The meetinghouse has since been turned into a Daughters of Utah museum, containing many artifacts from the Oregon Trail. Listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1980 and remains one of the best preserved colonies among some 500 established by leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints after their arrival in the Great Basin.

Image courtesy of the Chesterfield Foundation

From Memorial Day to Labor Day, visitors can visit (admission is free) from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m., Monday through Saturday, to trace the Oregon Trail’s ruts and touch walls that had held pioneer dreams. The Foundation’s work, detailed in National Park Service records, ensured the town’s story lived, a testament to families who refused to let their heritage fade.

Despite the snow keeping me at a distance, I didn’t need to touch the cabins to feel the weight of Chesterfield. The Calls, Tolmans, Reeses, and Yosts built a world here, only to watch it slip through their fingers. I’ll take the sound of the windmill with me, along with their stories, like a ghost that won’t let go.